Tracing Footsteps in a City - By visiting Prof. Ananya Roy

Publication date 25-08-2014

Her keen interest in traveling to Europe was not about luxury shopping or good food or beautiful scenery; it was primarily about art and literature. A brilliant student, she had tired of the study of economics and political science in college and had instead fallen in love with Bengali and English literature. Her self-directed passion was art: art from antiquity to postmodernism. Each summer I was schooled by her in the great works of art until they seemed as familiar to me as the frayed city of Kolkata. In preparation for her trip to Europe, she had prepared copious notes, meticulously planning each museum visit, reminding herself of every intricate detail of her favorite paintings. We can only imagine how much angst she caused for the guides and leaders of her budget tour! I remember that summer well because I spent it with my father in Kolkata. Well before the era of email and with international phone calls out of our financial reach, we relied on postcards from my mother. They punctuated the summer with tales of Europe, of her sheer delight in coming face to face with the masterpieces she had until now only seen in her collection of art books.

My life has been quite different than my mother’s. My academic engagements have kept me busy with a whirlwind of international travel such that I am usually glad to return to California, my home, as often as possible. But on my recent visit to the Centre for Urban Studies at the University of Amsterdam, I was reminded of my mother’s first visit to Amsterdam. Walking in the city, I saw myself as tracing her footsteps. I encountered the city not as a scholar of urbanism, but as the daughter of a high school teacher from India. I saw the city not as an urban planner but instead through the eyes of a global mind that had intimately studied the world to surpass the parochial boundaries of middle class life. I experienced the city not as postcolonial theorist, but rather in relation to the aspirations of my mother, her many educational accomplishments as well as her half-completed doctoral dissertation.

In Amsterdam, I came to a conclusion that I wanted to share with readers of this blog. It is this: that our urban experiences are always forged in relation to those we consider our ancestors, whether they are family or not. To walk the city is to trace their footsteps, whether we do so to obey or rebel. Such a relationship is not only a historical one but also a pedagogical one. We learn what the city is because we come to learn how others before us experienced the city. Amsterdam is an especially appropriate city for such lessons. In keeping with my mother’s passionate love for art, I spent many hours at the city’s unrivaled museums. First in line to enter the Rijksmuseum, I could feel her hand on my shoulder guiding me. But most of all, I took a step back to pay attention to why the act of going to a museum is such a vital part of modern urban life.

There is the sheer act of viewing; the push of the crowds; the sense of being part of humanity. But that moment in the museum is also one of profound modernity, of being able to understand ourselves relationally to time and space, the here and now as both continuity and rupture with elsewhere and the past.

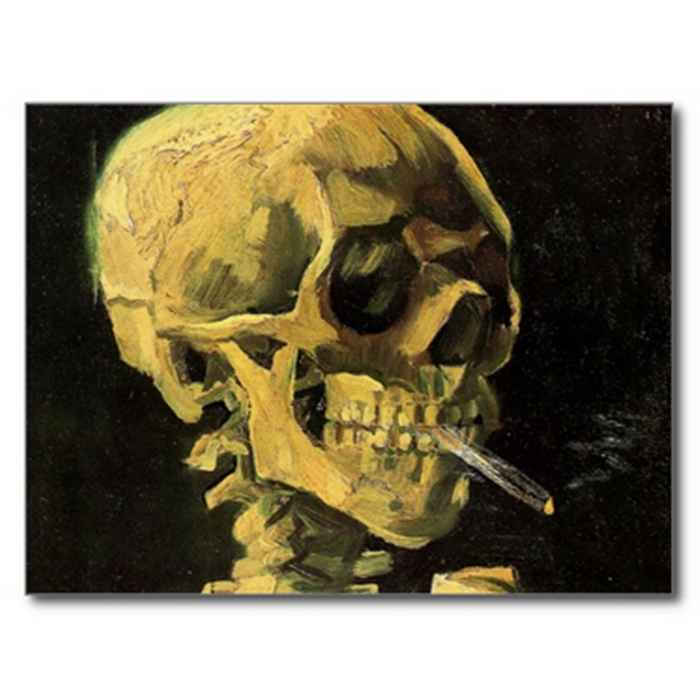

At the Van Gogh Museum, I bought my nephew, an American teenager about to head to college, a mug with this image on it. Painted by Van Gogh, it is titled “Head of a Skeleton with a Burning Cigarette.” I did so to register my displeasure with his new habit of smoking (he knows that I smoked – a lot - when I was in college) but also to make another point. Art historians tell us that Van Gogh most likely painted this unusual piece while enrolled in the art academy at Antwerp. Students at the academy were expected to render faithful portraits of the human body, drawing skeletons to master the human anatomy. Was the burning cigarette Van Gogh’s satire of this method of learning?

It was an appropriate image, I thought, for a nephew headed to college. Learning is not meant to be faithful replication; it is meant to be rebellious, satirical, irreverent. Yet, such rebellion can only be staged in relation to those we consider our ancestors. We know that Van Gogh developed his own stunning art in relation to that of the great artists who preceded him, including Rembrandt. For me, walking between the Van Gogh Museum and Rijksmuseum, was to trace these footsteps as well. In his letters to his brother, Theo, Van Gogh was to recount his time at the Rijksmuseum, his intimate study of the techniques of the old masters. In fact, for Van Gogh, the experience of Amsterdam was these intense moments in the museum. His unbounded enthusiasm, the sheer joy in his letters, reminds us that this is not the museum as a fossil of the past. This is the museum as present history. And so as I straggled out of the Van Gogh museum with the last batch of visitors on a balmy Amsterdam evening, I remembered my mother. Before I knew that the city of Amsterdam existed, before I could identify Europe on a map, before I was old enough to join school, I knew of sunflowers - but only those painted by Van Gogh. For me, there can be no Amsterdam that is not my mother’s city. For me, there can be no city that has not already been framed and viewed and studied and experienced by those in whose footsteps we must walk. A burning cigarette in hand is optional.

Ananya Roy

Ananya Roy is Professor of City and Regional Planning and Distinguished Chair in Global Poverty and Practice at the University of California, Berkeley. She teaches in the fields of urban studies and international development. Roy visited the Centre for Urban Studies mid April 2014 to give a special lecture on "Cities of the Asian Century. How Urbanism Became Slum-Free".