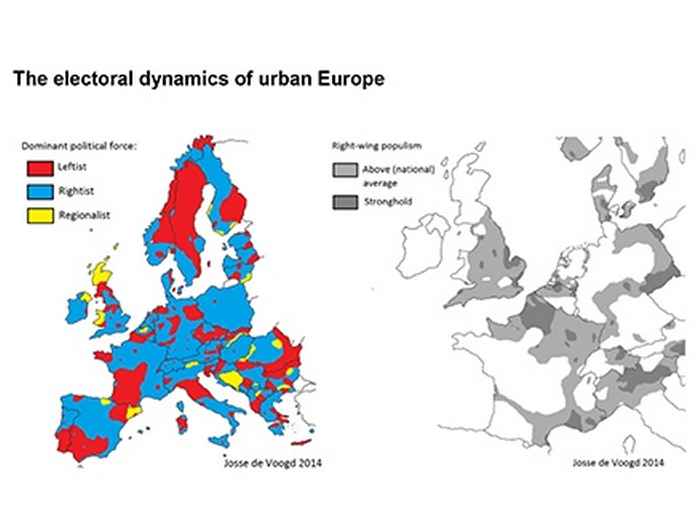

The electoral dynamics of urban Europe - by Josse de Voogd

Publication date 18-04-2016

A multicolored patchwork, that’s what the electoral map of Europe looks like. In a study published by World Policy Journal, I made a composition of all the political maps of the European countries together. This offers an intriguing insight in the different religiosities, class-differences, rivalries and lifestyles that are present. One of the main factors shaping this electoral geography is the divide between the urban, suburban and rural.