Living in the Pandemic City - by Fenne M. Pinkster

November 2020

It didn’t take long for the first commentaries to emerge in national and international media, heralding that Covid-19 might signal the end of the urban renaissance of the last decades. The dominant 21st century imaginary of cities as sites of creativity and innovation was replaced by a classic dystopian imaginary that depicts cities as particular sites of risk and stress for inhabitants. Indeed, as we all try to practice social distancing in close proximity to each other and many of us work from home through digital platforms and zoom meetings, the pandemic seems to threaten the fundamental social and economic functions of cities.

In such debates about the future and potential demise of cities, however, the experience of residents themselves is often overlooked. For them, the city is more than a place of innovation and creativity or of risk and contamination. It is also home. To understand how residents experienced living in the city under ‘intelligent’ lockdown in the first months of the pandemic, a survey was conducted in collaboration with researchers Laura de Graaff and Hester Booi from the Amsterdam municipal department for Research, Information and Statistics (OIS). We questioned whether and how the pandemic has led residents to reevaluate their home, neighbourhood and the city. The survey was distributed late June via an online City Panel and filled in by 1747 residents, generating a response rate of 56%. A Dutch report of the findings can be found here.

Contrasting experiences of home

On the one hand, keeping in mind the dystopian discourse on pandemic cities, the survey findings are cause for optimism. On average, Amsterdammers seem to have taken the pandemic in stride. Results show that in the early summer the impact of Covid-19 on feeling at home in the city and on intentions to move were minimal. The majority of residents (70%) went out daily, which was allowed even during the strictest lockdown period. Only 16% of the residents reported that they found this (somewhat) stressful and, strikingly, only a very small share of Amsterdammers was concerned about actually becoming infected, which probably is related to the fact Covid-19 was in fact not so widespread in the city. Lastly, findings show that there is a large group of residents that evaluated the staying-home period quite positively (41%), rediscovering their neighbourhood and enjoying the conviviality in the city.

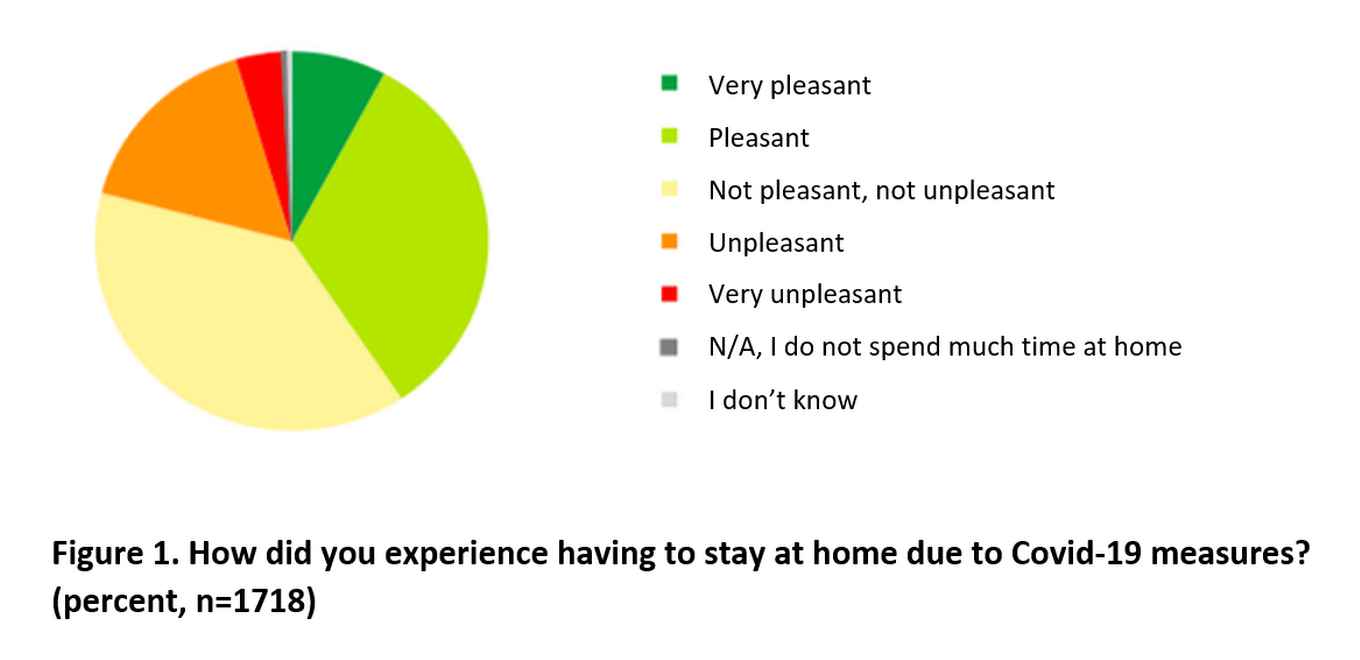

On further exploration, however, the results are also cause for concern: they show that not everyone shared this positive experience of the lockdown (see figure 1). There is a smaller group of residents who evaluated this period much more negatively (25%), citing substantial loneliness, living in suboptimal housing conditions and concerns about lack of social distancing and fear of contamination in public spaces as their main reasons. These contrasting experiences emerge at the intersection of class, age and life course, exposing a distinction between residents who were able to fall back on a stable housing, family and health situation and residents for whom the pandemic heightened their awareness of their already precarious living situation.

Consequently, while the stay-at-home period seems to have served as a confirmation of their comfortable place in the city for some residents, for others it has destabilized their sense of home. In this last group, low educated residents, renters, residents in more peripheral and marginal neighbourhoods, singles, younger residents and residents with health problems are overrepresented, although for different subgroups negative experiences of the lockdown seem to be triggered by different mechanisms. For example, the negative experiences of younger Amsterdammers in their twenties and early thirties, living alone in smaller housing, seem related to feelings of loneliness under lockdown and doubts about their ability to find a suitable place for themselves in the city. The reticence of this group to retreat into their homes during the current second lockdown can perhaps be seen as a mirror to these negative experiences in the spring. In contrast, concerns about health and experiences of stress going outdoors seemed more important in shaping the experiences of low educated residents, older residents and residents of ethnic minority backgrounds. Follow-up qualitative interviews will be conducted to explore these differentiated experiences further.

Rediscovering the neighbourhood

Such contradictory experiences are particularly important to reflect on considering the positive depictions of Amsterdam in local news sites like Parool and AT5 at the start of the pandemic. These selectively represent the experience of particular groups of residents, who appreciated the first lockdown as a period in which they found new ways to engage with their surroundings. A first element of this story is the (re)discovery of the neighbourhood by residents who pre-Covid used to spend very little time there. This concerns a group of high educated, relatively young respondents, who in the survey described the first lockdown period as a nice break from their normally hectic lives and busy schedules. These residents used their time at home to discover the various facilities offered by their neighbourhood, including specialty shops and take-out from restaurants nearby under the umbrella of #supportyourlocal initiatives on social media. Their engagement with the local was also expressed materially, through small-scale, bottom-up investments in the urban landscape, ranging from small gardening-projects in front of people’s houses to new street benches and picknick tables on sidewalks where they could meet and chat with formerly unknown neighbours. In the survey, this class-based experience of the lockdown is expressed in a positive reevaluation of the neighbourhood by almost a quarter of the respondents (22%).

Reconquering the city

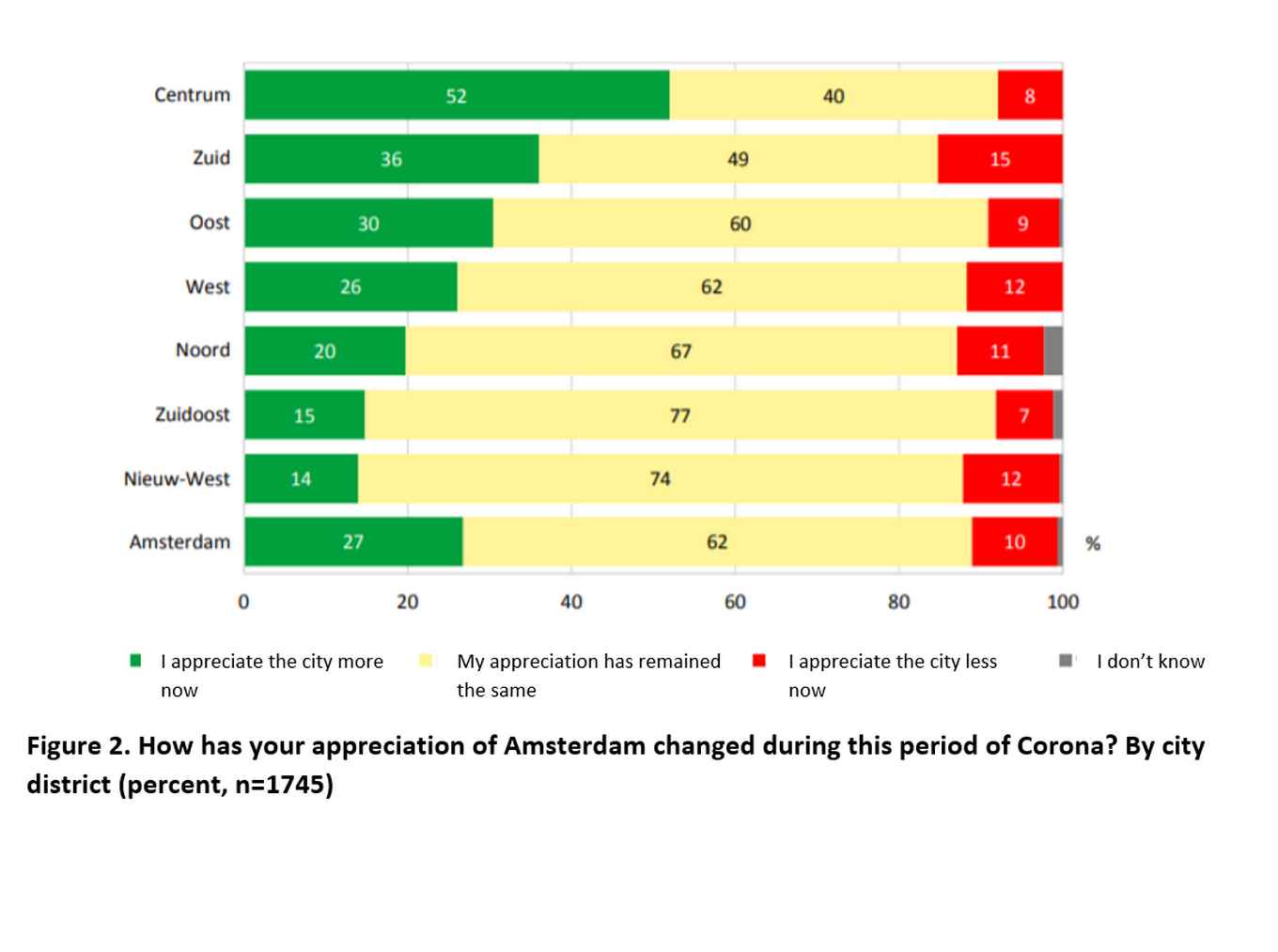

A second element in this story about pandemic Amsterdam is the reappreciation of the city as a whole. A substantial share of respondents (27%) indicated that they appreciated the city more than before Covid-19. This experience is highly differentiated across the city and is most strongly associated with living in the historic district as well as adjacent, centrally located neighbourhoods (see figure 2). This positive evaluation of the city under Covid-19 can only be understood in light of the increasingly negative narratives about commodification of the city and over-tourism in the famous Canal Belt in the past decade (Pinkster & Boterman 2017). For many respondents, the sharp reduction of tourism felt as a reconquering of the city for Amsterdammers. An often read comment in the survey was that Amsterdammers could finally experience the beauty of their own city, without being run over by tourists on bikes. Yet there is more to this sentiment than tourism, as it is also expressed in other centrally located neighbourhoods. It seems to be related to the overall densification in the city in the past decades - with the streets becoming more crowded due to more residents and more traffic – and the increasing dominance of consumption in the use of urban space in some of the other centralized neighbourhoods. From this perspective, many Amsterdammers experienced the pandemic as a much needed break away from these developments and many respondents noted they particularly appreciated the quiet. However, these positive effects are most strongly felt in the more central and more affluent parts of the city and in this respect might be seen as a form of urban revanchism.

Implications for the current lockdown

As a final point of critical reflection, an important question is to consider how sustainable some of the positive experiences of Amsterdam in the early months of the pandemic might be. The survey was conducted in a time when Covid-19 was not widespread in the city and perhaps represented more of an abstract threat than a real one. Few people were forced to quarantine entirely and there seems to have been a strong cumulative effect between positive experiences of the home and being able to enjoy neighbourhood and the city at the start of spring and early summer. In the current second lockdown, with many more infections in the city, more Amsterdammers will be confronted with having to stay indoors entirely and Covid-19 entering their homes.

In addition, going outdoors as an escape of staying home may be experienced as far more stressful due to increase in infections and is certainly less attractive in the winter time. Lastly, it can be hypothesized that the newness of the positive reevaluation of the neighbourhood and the city may be wearing off as some people find themselves increasingly missing the types of activities that match their previous urban lifestyles. All of these might lead to more negative experience of home in the current semi-lockdown and considering our survey findings we can expect this to affect in particularly the more precarious and less established groups in the city.

Fenne Pinkster is Associate Professor of Urban Geography. Her research agenda concerns the geography of everyday urban life.

This research project has been made possible by OIS Amsterdam and a Center for Urban Studies Teaching Buy-out grant.