Reclaiming mobility innovations from boring solutions

By: Marco te Brömmelstroet and Anna Nikolaeva

We see that digital innovations in this field are greeted with eager optimism: a belief in technological solutionism combined with an increasingly fierce globalized battle for venture capital fuels a highly volatile quest for ‘unicorn solutions’: fail big and fail fast. Firstly, because of this, innovations come up and quickly start dominating social and political discourses. When new innovations come forward, academic debates often centre around ‘how’-questions and are dominated by engineers and technological domains.

In such dynamics, potential dangerous and perverse impacts of the implementation of such innovations only receive attention once they are alarming and, in some cases, appear to be out of control. Secondly, societal debates on smart mobility are not focusing on radical change and instead revolve around incremental changes, often ignoring the very issues that have generated unsustainable and unfair mobility regimes in the first place. These two observations highlight the importance of making critical academic discussions more visible in society and of increasing meaningful interactions between academia and practice.

What do these innovations mean in terms of the larger societal effects? How do they affect the way that people engage with each other and with their wider social and spatial environment? How do they influence existing mobility practices and mobility politics? Which problems do these innovation help solve, if at all? Can they also have negative impacts? And how to cope with inevitable uncertainties?

Beyond Technosolutionism

In the academic seminar organised with these questions in mind by the Urban Mobility Futures Chair of the University of Amsterdam, a group of international scholars exchanged ways to better understand the dynamics of urban mobility innovation.

Miloš Mladenović from Aalto University discussed how current processes of technological innovation are influenced by path dependent choices of what types of knowledge are acceptable, what kinds of worldviews dominate, and which values have become solidified. In his experiences with being involved as an expert for the European Commission to develop new recommendations for driverless mobility, he found an institutionalized form of technological determinism: driverless mobility will become a reality and the only discussion should be about how to increase trust throughout society to make it happen. Issues such as safety, privacy and fairness were narrowly defined within this logic. Mladenovic calls for rethinking the Western epistemology and increase the value of other types of knowing, other disciplines and revalue emotions. We might need collective empathy, imagination and systems thinking.

A more general reflection on the nature of “smart” mobility innovations was given by António Ferreira from the University of Porto. What he calls the "smart innovation factory" is, for anyone who cares to observe it with a critical eye, a strategy for doing exactly the same for almost two decades: instead of solving wicked problems through the creation of true and useful novelties, it is simply converting a growing number of existing and time-tested objects (from toothbrushes to cars, from phones to vacuum cleaners) into so called "smart" innovations.

This happens by means of applying what António Ferreira calls the “seven monotonous principles of smart innovation”: electrification, digitization, webification, datafication, personalization, actuation, and marketization. An example of this process is the creation of a smart toothbrush: from a simple and unexpensive, yet perfectly functional object that requires no electricity to brush teeth, it created a complex electric appliance that does exactly the same thing as before (brushing teeth), but with more issues of privacy and dependence on electricity and smart phones.

Such pseudo-innovations fail to do what is most needed: promote a transition away from resource- and energy-intensive social practices. When considering this problematic state of affairs, two key questions emerge. First, can innovators still innovate, or has their creativity been neutralized by the dominant regime of the smart innovation factory? Second, can innovators still re-align their work with the public interest? António Ferreira asks them to move out from the smart innovation straightjacket and explore again truly innovative possibilities in the name of sustainability and the public interest.

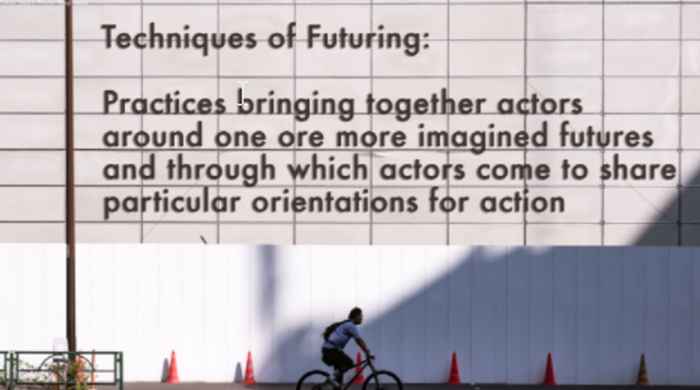

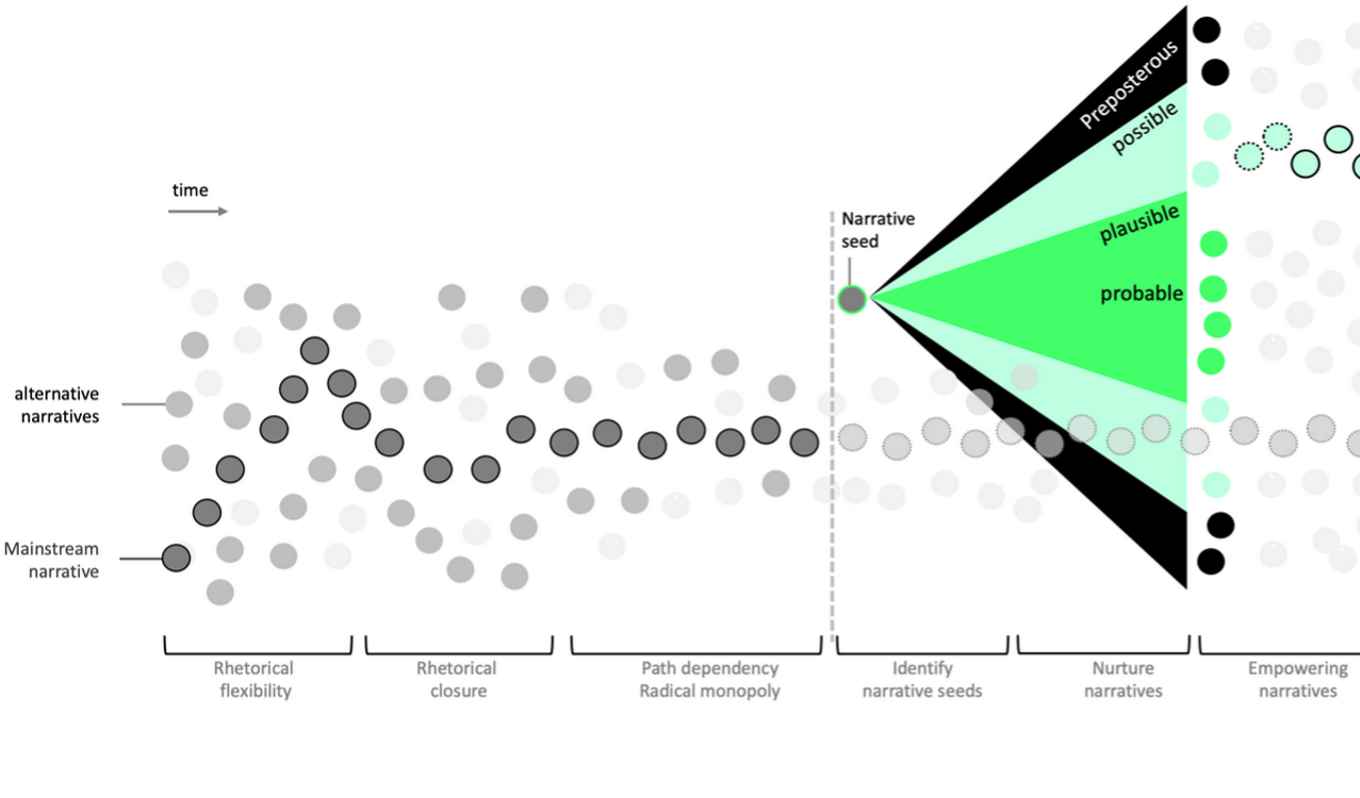

How does radical change in mobility systems happen? And what is exactly the role of imaginaries in the way that we think and do towards those mobility futures? With a powerful visual presentation Maarten Hajer (Utrecht University) took us into his ideas about the answers to these questions (and raising a few more). He introduced us to the upcoming Academy of Hope where such questions will be central in teaching and research.

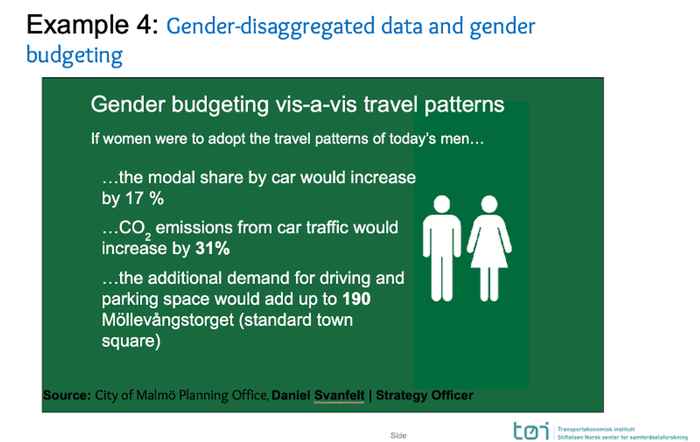

Tanu Priya Uteng (TØI) brought our attention to questions of diversity in the human population and inequalities that are (not) targeted with current mobility innovations such as mobility hubs. She made a clear case that we need to look more closely to how they can serve the specific mobility needs of women and older adults. Often mobility innovations ignore the needs of these groups or even explicitly cater to other groups.

Interestingly, women in particular, on average show more sustainable mobility patterns then men do (see the image below), which means that ignoring their mobilities is not only exclusionary – it also means missing important chances and alternative paths for mobility futures.

Mentioning 'guinea pigs’ just a bit too often (😉), Kate Pangbourne (ITS Leeds) took us into the world of the leaders of the mobility innovation domain and discussed in what ways their leadership, their ways of seeing the world and the business models that they have normalised are deeply problematic. She also problematised technological solutionism in the mobility innovation industry that acts as a distraction from various solutions and ideas that already exist and can potentially bring closer a “civilised decarbonised future”.

Avigail Ferdman (Israel Institute of Technology/JDC-ELKA) proposed a more holistic ‘human capacities’ framework to better understand the full range of impacts that mobility innovations can have on our collective wellbeing. Applying this to the presented imaginaries of self-driving cars lead her to conclude that they do not offer us conditions for realising the full spectrum of our human capacities, quite the opposite. Often imagined as single-occupancy “bubbles” meant for work or entertainment self-driving cars may offer us a very reductive experience compared to other ways of moving through places which engage one’s senses a broader range of human capacities.

We are very grateful for the contributions by Hebe Verrest (University of Amsterdam) and Federico Savini (University of Amsterdam) as additional referents to our discussion.

A movement to rethink mobility innovation

Next to bringing together this excellent group of academic thinkers and the potential collaborations and networks that this brings, there were also a number of conclusions that could be drawn from the discussion: (1) there is an urgent need for more engagement of social scientists in processes of urban mobility innovation; (2) current innovation practices are mostly about tinkering with objects instead of solving real-world problems; (3) we need to develop more holistic frameworks to understand both the different societal needs for and the impacts of urban mobility innovations.

One pathway to work on bringing these observations forward was discussed in the afternoon. Marco te Brömmelstroet (University of Amsterdam) and Anna Nikolaeva (University of Amsterdam) are working together with Edenspiekermann on the ‘Laboratory of Thought: the movement to rethink urban mobility innovations’. Key players in mobility innovation from the public, private, academic and civic sector join the Laboratory of Thought to train their cognitive leniency; they learn to identify new narrative seeds, nurture them into new mobility narratives and empower these through radical innovations. The Laboratory of Thought will be launched in June 2022.