The designer bike as a signifier of whiteness

by Rozemarijn Weyers

But first and foremost, we need to ask ourselves: what is whiteness? In Peake’s words, whiteness is a way of being in the world, a set of cultural practices to be drawn upon, often not named as ‘white’ by white people but instead looked at as normal or natural. It is more than just a skin color: positioned as the overarching norm from which all other racialized categories are perceived and understood, it operates as a position of structural advantage and privilege. The meaning of whiteness differs per historical and geographical context, making it a difficult concept to explain with precision. Nevertheless, none of this negates the very real effects it has on people’s lives – something the substantial turnout at the protests in Amsterdam Zuidoost last year showed.

Whiteness in the Netherlands

Despite its ubiquity, whiteness cannot be theorized as a universal category and should thus be positioned in specific geographical and social systems of racialization. For the Netherlands, this means that the notion of whiteness must be placed in a discourse that is reluctant to acknowledge ‘race’ as a formal category. As Gloria Wekker explains in her book White Innocence, (white) Dutch people claim to be ‘color blind’, which is often accompanied by an ignorance of the structural and institutional aspects of white privilege and racism.

But what does whiteness look like in the context of the Netherlands? In this blog, based on the song ‘Designer Fiets’ (‘Designer Bike’) by Massih Hutak, I would like to point out two starting points for thinking about Dutch whiteness. In the song, the Afghan-Dutch writer, activist and rapper critiques the gentrification processes occurring in Noord (the North of Amsterdam). In doing so, he points to several elements that constitute whiteness, of which I will elaborate on two that specifically relate to the urban context.

Two stills from the video clip ‘Designer Fiets’ by Massih Hutak: on the left are the white gentrifiers of Noord (2019: 1:33) and on the right the old residents of Noord (Ibid.: 2:20)

Mobility as a way of belonging

Gentrification processes aim at social and economic change in the multi-ethnic working-class neighborhoods of Noord. In Designer Fiets, Hutak contrasts the lifestyle of the white upper-middle class gentrifiers, symbolized by their use of designer- and cargo-bikes, with that of the original residents of Amsterdam Noord who drive Cantas (see figure 1 and figure 2). A recent study conducted by Boterman also shows how specific forms of cycling are increasingly becoming highly distinctive practices that are associated with specific social positions. In the Dutch context, where cycling is so common that it is seen as part of a national habitus and therefore a quintessential part of Dutchness, not cycling may be construed as being out of place or otherness. Designer- and cargo-bikes, as opposed to Cantas, become loaded with symbolic meanings that represent ‘Dutchness’ and especially white Dutch identities. In this way, the way you move around the city becomes part of the everyday practices of belonging that are associated with processes of inclusion and exclusion.

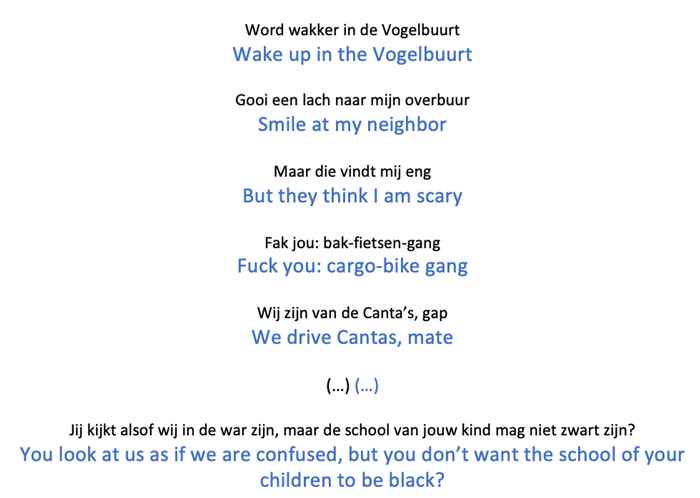

Excerpt 1 of the song ‘Designer Fiets’ by Massih Hutak (translation by author)

Columbus Syndrome

In his lyrics (see figure 3), Hutak compares Columbus, who sailed to the Americas and thereby started the era of European colonization, to the gentrifiers who cross the IJ from the “mainland” of Amsterdam to the “unexplored” Noord. The Columbus Syndrome points to the perceived attitude of the white gentrifiers, who see themselves as pioneers that enter a terra incognita and tend to forget that this neighborhood was already inhabited by other (racialized) groups. Part of the Columbus Syndrome is the occupation of “the land” without caring about or adapting to existing neighborhood structures and practices of the residents. The white identity of the gentrifiers in this case thus becomes constructed in relation to the history of the Netherlands as a colonizing nation.

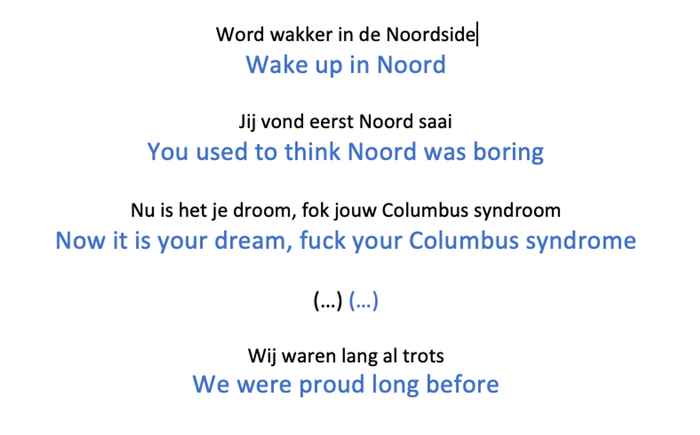

Excerpt 2 of the song ‘Designer Fiets’ by Massih Hutak (translation by author)

Figure 4 Left: Newly built houses in Amsterdam Noord; right: ‘Van der Pek’ neighborhood in Noord (Hutak 2019)

All in all, in the song Designer Fiets by Massih Hutak, whiteness is (de)constructed in relation to cultural, social and economic differences in lifestyle between the gentrifiers and the original residents of Noord. This points to the complexity and intersectionality of whiteness with other factors, such as class and cultural background. By further researching and conceptualizing white spaces in Amsterdam this academic year, I hope to push the theoretical, empirical and societal conversation about (geographies of) whiteness forward. If you want to get involved, share experiences or thoughts, please do not hesitate to get in touch.

Rozemarijn Weyers is a Research Master student Urban Studies. During an apprenticeship under the supervision of Rivke Jaffe she worked on urban geographies of whiteness and explored how white identities become normative and invisible – or conversely, contested and destabilized – through socio-spatial processes in cities.