Mega Cities Projects: the Case of Port of Spain - By Hebe Verrest

Publication date 28-09-2015

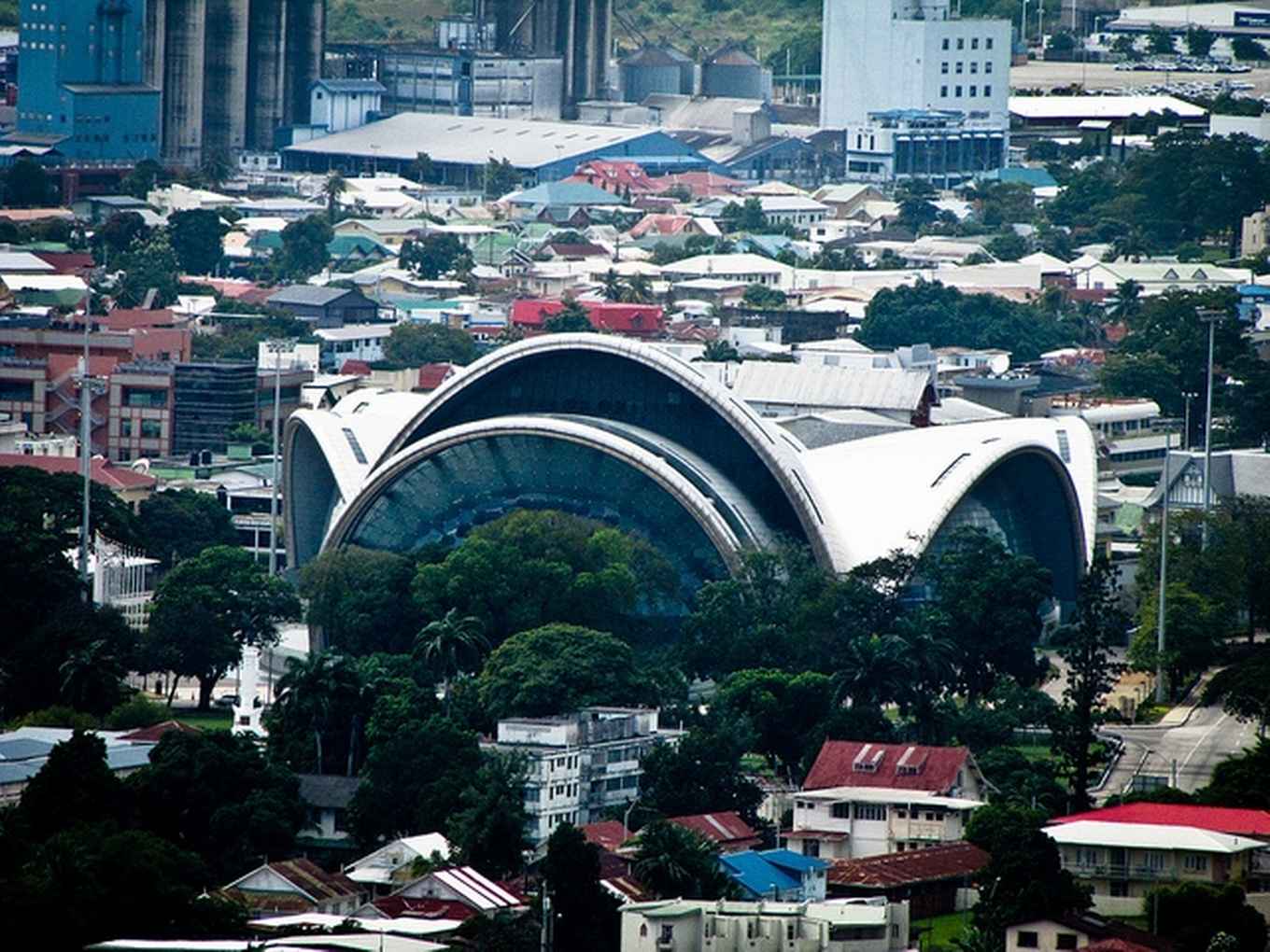

One of such cities is Port of Spain, the capital of the Caribbean Republic of Trinidad and Tobago. Since 2002, I have visited and studied Port of Spain multiple times. This period conflates with a period of major urban transformation of the city. The countries’ buoyant economy, resulting from large oil and gas reserves, created financial reserves for the state and attractiveness for foreign capital. This, and the ambitions to make Port of Spain the financial heart of the region, the home to the head quarters of the (not-materialized) FTAA headquarters and realize the status of ‘developed’ nation by 2020, paved the way for this major change in the urban face of Trinidad and Tobago. Port of Spain, so to say, was to become a Saskia Sassen style global city within the Caribbean, topping the ranks of urban areas in the region. Whereas up to the millennium turn the local “Twin Towers”, housing the Ministry of Finance, were the highest and one of the few high rise buildings in the city, today’s skyline is marked by multiple skyscrapers, housing hotels, offices of oil companies, luxury apartments and many government offices. The cities’ 20 km long waterfront especially, boarding the Atlantic Ocean, underwent a complete metamorphose. It includes the International Waterfront Center, an area housing a Hyatt hotel, two (largely empty) sky-scrapers meant for government offices and a pedestrian boulevard, on what used to be the Port of Spain port. Across the street, the so called Government Campus displays multiple enormous government buildings, most of them largely empty.

In understanding the why, the how and the consequences of such transformation a Jennifer Robinson ordinary city approach, which explains urban transformations from local economic, political and social configurations is warranted as it allows to understand the global city of Port of Spain in the local context of Caribbean postcolonial, small island development states.

One of such local configuration is the governance practice. Analyzing practices underpinning the Waterfront transformation shows nothing of classic understanding of neoliberal cities such as a retreating state or decentralization. The picture based reveals that a few powerful individuals within the central state and the private sector push the agenda for transformation at every stage of the project. As one interviewee said: “one morning the prime minister woke up and decided he wanted the Waterfront, he then phoned his friends, and….”. Furthermore, in favor of foreign companies, the local private sector is largely excluded from the development of the area. However, the strong dependence of local engineers, architects and builders on the government for work, stops them from expressing critiques.

Participation from other actors was minimal, except for one event. Massive public protest was initiated when the building of the Waterfront required the closing down of the “breakfast shed”. This immensely popular, cheap restaurant served traditional dishes to port workers and civil servants working in the area but also to other Trinidadians from all backgrounds. The government had to give in and as a result one finds next to the fancy Hyatt hotel, impressive skyscrapers, a rather simple, basic structure, providing selling space to the “Femmes du Chalets”, referring back to the original patois name of the Breakfast Shed.

Hebe Verrest

Hebe Verrest is a Human Geographer, with a specialisation in Human Geography of Developing Countries. As off 2010 she is assistant professor (UD) at the Department of Geography, Planning and International Development Studies (GPIO) of UvA. Her research focuses on small and medium sized cities, particularly in The Caribbean. Leading in her work is a focus on exclusion and inequality. These come back in the more specific themes that she conducts research on: urban governance and spatial planning, climate change, livelihoods and entrepreneurship.