How middle-class cities emerged under social democratic rule

30 March 2023

From being proud on social rent projects in the 1980s to being proud on prestigious upper middle-class residential complexes 40 years later, like those in the docklands of East-London or Pontsteiger in Amsterdam. This pride in developing ‘luxurious living’ symbolically marks the transformation of cities in the global North, argue Boterman and Van Gent. But how could a city like Amsterdam, that has been ruled by social democratic parties for over a century, and that is internationally famed for its social policies, become a place dominated by middle-class interests and where gentrification sets the tone?

In their new book ‘Making the Middle-class City’ Boterman and Van Gent present a new model for analyzing socio-spatial urban change and reveal the mechanisms behind the transformations of working-class cities into cities of which its economic base now rests on financial, business and consumption services. Cities where highly educated and increasingly affluent people have come to dominate public, cultural and social life and the urban landscape. ‘It was a contingent process that cannot be reduced to national and global processes alone, as it has been very much a local political affair too.’

Economic restructuring & changing social class

Boterman and Van Gent trace the change in planning and housing policy to the shift from a mixed economy with a strong basis in manufacturing to a predominantly service-based economy. ‘In the 1990’s the appearance of new investments and residents was a welcome sight after years of urban crisis. The impoverished and unpopular city was turning into a growing “magnet for talent”. Like in many other cities, this resulted in the emergence of a new social class structure.’

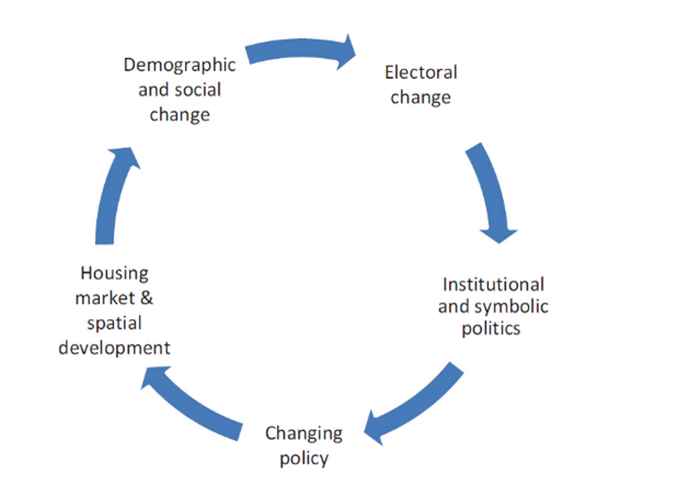

Boterman and Van Gent argue that these demographic and social class changes are however also connected to new urban politics. They show how the changing social geography of cities led to a new balance of power through electoral dynamics and through changing institutional and symbolic politics. ‘Urban policies aimed at the highly educated, like the construction of owner-occupied housing, facilitated a stronger influx of highly educated households in a city like Amsterdam. In turn through the electoral influence of these highly educated inhabitants, for example whom they voted for, this led to more political representation of their interests as well as the increasing symbolic dominance of middle class values and practices’, explain the authors, ‘like values of diversity and cosmopolitanism or school choice and consumption practices.’

Socio-spatial and political feedback loops

Boterman and Gent conclude that social, spatial and political transformations come to reinforce each other in feedback loops. ‘Not only policies, but also the ideologies of the local state change. The gentrification of Amsterdam affects and gentrifies its political landscape: politicians and policy makers increasingly represent middle-class interests and build a city that is much more welcoming to highly educated, affluent citizens than to the working classes.’

An ongoing story

Boterman and Van Gent state that the socio-political cycle of urban change that has functioned as an engine of urban transformation will continue to shape cities like Amsterdam in the future. ‘Urban transformation is an ongoing process. The middle-class city as we have discussed it in our book is not the teleos, the end of its history. The urban politics which developed in Amsterdam between the 1980s and the 2010s will continue to shape the city.’

Contact

For questions please contact:

Book details

Willem Boterman and Wouter van Gent, 2023, ‘Making the Middle-class City. The politics of gentrifying Amsterdam’, London: Palgrave MacMillan. Go to the publisher website

Book presentation (in Dutch)

Tuesday 4 april Boterman and Gent will present their book in Pakhuis De Zwijger (in Dutch). More information on this book presentation